Affect disorders. Epilepsy.

Cyclothymia

Cyclothymia or "cycloid temperament," is a chronic disorder acterized by the sequential appearance of periods of very mild lie symptoms and periods of mild depressive ones. Although in likelihood it represents a forme fruste of bipolar disorder, it is onsidered, in deference to current DSM-IV usage, in its own hapter.

Prevalence figures for cyclothymia range from 0.4% to 1%; it is obably equally common among males and females.

CLINICAL FEATURES

manic and depressive periods typically alternate in an ar fashion, lasting for days or weeks; the euthymic intervals ³ the periods range in duration from a month or more to > or less. Indeed in some cases, no euthymic interval exists at nd the patient demonstrates continuous cycling, uring manic periods patients may be enthusiastic and over- or at times irritable.

COURSE

Cyclothymia is a chronic disorder; in some patients it may be lifelong.

COMPLICATIONS

Some patients, particularly if their symptoms are mild, may escape complications entirely. Indeed, as noted earlier, some, thrust along by their mild manic symptoms, may succeed brilliantly.

ETYOLOGY

As noted in the introduction, cyclothymia is probably a forme fruste of bipolar disorder. The prevalence of bipolar disorder is increased among the biologic relatives of patients with cyclothymia as compared to the relatives of controls.

Manic episode of stage I or greater intensity, or a full depressive one, in which case the diagnosis is revised to bipolar disorder.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Certain patients with borderline or histrionic personality disorder may at times present such a tumultuous clinical picture as to suggest cyclothymia. In personality disorders, however, mood changes are always intimately and inextricably tied to events in the patient's life.

By contrast, in cyclothymia, the mood changes are autonomous and independent from changes in the patient's life. However, some patients may have both a personality disorder and cyclothymia, with their mood changes at times bound up with, and at times autonomous from, events around them.

In adolescence, cyclothymia may lead to extreme misconduct, suggesting a diagnosis of conduct disorder.

Similar mood changes may occur as either a lengthy prodrome to bipolar disorder or as residual symptoms in the interval between full-blown manic episodes.

Affective disorders. Bipolar Disorder

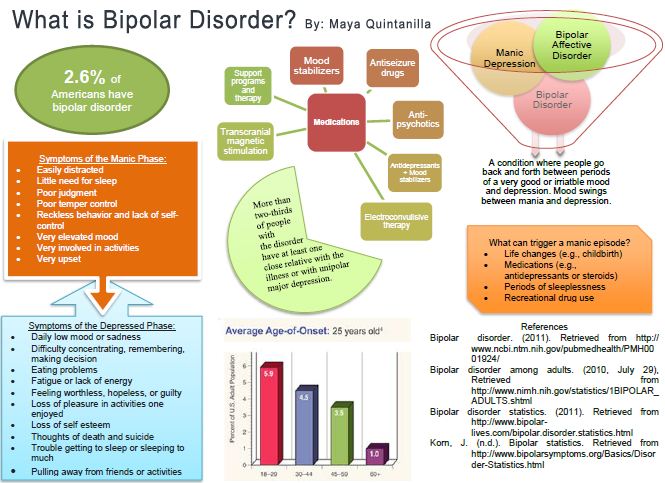

bipolar disorder is characterized by the occurrence of at least one manic or mixed-manic episode during the patient's lifetime. Most its also, at other times, have one or more depressive episodes, intervals between these episodes, most patients return to |ir normal state of well-being. Thus bipolar disorder is a "cyclic" |f periodic" illness, with patients cycling "up" into a manic or d-manic episode, then returning to normal, and cycling n" into a depressive episode from which they likewise eventually or less recover. Bipolar disorder is probably equally common among men and women and has a lifetime prevalence of from 1.3 to 1.6%.

Bipolar disorder in the past has been referred to as "manic depressive illness, circular type." As noted in the introduction to the chapter on major depression, the term "manic depressive illness," at least in the United States, has more and more come to be used as equivalent to bipolar disorder. As this convention, however, is not worldwide, the term "bipolar" may be better, as it clearly indicates that the patient has an illness characterized by "swings" to the manic "pole" and generally also to the depressive "pole."

ONSET

Bipolar disorder may present with either a depressive or a manic episode, and the peak age of onset for the first episode, whether depressive or manic, lies in the teens and early twenties. Earlier onsets may occur; indeed some patients may have their first episode at 10 years of age or younger. After the twenties the incidence of first episodes gradually decreases, with well over 90% of patients having had their first episode before the age of 50. Onsets as late as the seventies or eighties have, though very rare, been seen.

Premorbidly, these patients may either be normal or display mild symptoms for a variable period of time before the first episode of illness.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The discussion of signs and symptoms proceeds in three parts: first, a discussion of a manic episode; second, a discussion of a depressive episode; and, third, a discussion of a mixed-manic episode.

Manic Episode

The nosology of the various stages of a manic episode has changed over the decades. In current DSM-IV nomenclature, hypomanic episodes are separated from the more severe full manic episodes, which in turn are characterized as either mild, moderate, severe, or severe with psychotic features. Kraepelin, however, divided the "manic states" into four forms—hypomania, acute mania, delusional mania, and delirious mania—and noted that his observation revealed "the occurrence of gradual transitions between all the various states." In a similar vein, Carlson and Goodwin, in their elegant paper of 1973, divided a manic episode into "three stages": hypomania, or stage I; acute mania, or stage II; and delirious mania, or stage III. As this "staging" of a manic episode is very useful from a descriptive and differential diagnostic point of view, it is used in this chapter. Thus, when the term "manic episode" is used it may refer to any one of the three stages of mania: hypomania, acute mania, or delirious mania.

Manic episodes are often preceded by a prodrome, lasting from a few days to a few months, of mild and often transitory and indistinct manic symptoms. At times, however, no prodromal warning signs may occur, and the episode starts quite abruptly. When this occurs, patients often unaccountably wake up during the night full of energy and vigor—the so-called "manic alert."

The cardinal symptoms of mania are the following: heightened mood (either euphoric or irritable); flight of ideas and pressure of speech; and increased energy, decreased need for sleep, and hyper-activity. These cardinal symptoms are most plainly evident in hypomania. In acute mania they exacerbate and may be joined by delusions and some fragmentation of behavior, and in delirious mania only tattered scraps of the cardinal symptoms may be present, otherwise being obscured by florid and often bizarre psychotic symptoms. Although all patients experience a hypomanic stage, and almost all progress to at least a touch of acute mania, only a minority finally are propelled into delirious mania. The rapidity with which patients pass from hypomania through acute mania and on to delirious mania varies from a week to a few days to as little as a few hours. Indeed, in such hyperacute onsets, the patient may have already passed through the hypomanic stage and the acute manic stage before he is brought to medical attention. The duration of an entire manic episode varies from the extremes of as little as a few days or less to many years, and rarely even to a decade or more. On the average, however, most first episodes of mania last from several weeks up to 3 months. In the natural course of events, symptoms tend to gradually subside; after they fade many patients feel guilty over what they did and perhaps are full of self-reproach. Most patients are able to recall what happened during hypomania and acute mania; however, memory is often spotty for the events of delirious mania. With this brief general description of a manic episode in mind, what follows now is a more thorough discussion of each of the three stages of mania.

Hypomania. In hypomania the mood is heightened and elevated. Most often these patients are euphoric, full of jollity and cheerfulness. Though at times selfish and pompous, their mood nevertheless is often quite "infectious." They joke, make wisecracks and delightful insinuations, and those around them often get quite caught up in the spirit, always laughing with the patient, and not at him. Indeed, when physicians find themselves unable to suppress their own laughter when interviewing a patient, the diagnosis of hypomania is very likely. Self-esteem and self-confidence are greatly increased. Inflated with their own grandiosity, patients may boast of fabulous achievements and lay out plans for even grander conquests in the future. In a minority of patients, however, irritability may be the dominant mood. Patients become demanding, inconsiderate, and intemperate. They are constantly dissatisfied and intolerant of others, and brook no opposition. Trifling slights may enrage the patient, and violent outbursts are not uncommon. At times, pronounced lability of mood may be evident; otherwise supremely contented patients may suddenly turn dark, churlish, and irritable.

In flight of ideas the patient's train of thought is characterized by rapid leaps from one topic to another. When flight of ideas is mild, the connections between the patient's successive ideas, though perhaps tenuous, may nonetheless be "understandable" to the listener. In somewhat higher grades of flight of ideas, however, the connections may seem to be illogical and come to depend more on puns and word plays. This flight of ideas is often accompanied by pressure of thought. Patients may report that their thoughts race, that they have too many thoughts, that they run on pell-mell. Typically, patients also display pressure of speech. Here the listener is deluged with a torrent of words. Speech may become imperious, incredibly rapid, and almost unstoppable. Occasionally, after great urging and with great effort, patients may be able to keep silent and withhold their speech, but not for long, and soon the dam bursts once again.

Energy is greatly, even immensely, increased, and patients feel less and less the need for sleep. They are on the go, busy and involved throughout the day. They wish to be a part of life and to be involved more and more in the lives of those around them. They are strangers to fatigue and are still hyperactive and ready to go when others must go to bed. Eventually, the patients themselves may finally go to sleep, but within a very brief period of time they then awaken, wide-eyed, and, finding no one else up, they may seek someone to wake up, or perhaps take a whistling stroll of the darkened neighborhood, or, if alone, they may spend the hours before daybreak cleaning out closets or drawers, catching up on old correspondence, or even paying bills.

In addition to these cardinal symptoms, hypomanic patients are often extremely distractible. Other conversations and events, though peripheral to the patients' present purposes, are as if glittering jewels that they must attend to, to take as their own, or simply to admire. In listening to patients, one may find that a fragment of another conversation has suddenly been interpolated into their flight of ideas, or they may stop suddenly and declare their unbounded admiration for the physician's clothing, only then again to become one with the preceding rush of speech.

Hypomanic patients rarely recognize that anything is wrong with them, and though their judgment is obviously impaired they have no insight into that condition. Indeed, as far as hypo-manic patients are concerned, the rest of the world is sick and impaired; if only the rest of the world could feel as they do and see as clearly as they do, then the rest of the world would be sure to join them. These patients often enter into business arrangements with unbounded and completely uncritical enthusiasm. Ventures are begun, stocks are bought on a hunch, money is loaned out without collateral, and when the family fortune is spent, the patient, undaunted, after perhaps a brief pause, may seek to borrow more money for yet another prospect. Spending sprees are also typical. Clothes, furniture, and cars may be bought; the credit card is pushed to the limit and checks, without any ³ foundation in the bank, may be written with the utmost alacrity. Excessive jewelry and flamboyant clothing are especially popular. |The overinvolvement of patients with other people typically leads ³ the most injudicious and at times unwelcome entanglements, ssionate encounters are the rule, and hypersexuality is not ncommon. Many a female hypomanic has become pregnant dur-; such escapades. If confronted with the consequences of their ehavior, hypomanic patients typically take offense, turn perhaps bdignantly self-righteous, or are quick with numerous, more or plausible excuses. When hypomanic patients are primarily able rather then euphoric, their demanding, intrusive, and [judicious behavior often brings them into conflict with others I with the law.

Acute Mania. The transition from hypomania to acute mania irked by a severe exacerbation of the symptoms seen in hypo-ilia, and the appearance of delusions. Typically, the delusions grandiose: millions of dollars are held in trust for them; sby stop and wait in deferential awe as they pass by; the Ident will announce their elevation to cabinet rank. Religious sions are very common. The patients are prophets, elected by a magnificent, yet hidden, purpose. They are enthroned; I God has made way for them. Sometimes these grandiose iions are held constantly; however, in other cases patients may ily boldly announce their belief, then toss it aside with :r, only to announce yet another one. Persecutory delusions > appear and are quite common in those who are of a pre-fiantly irritable mood. The patients' failures are not their own : results of the treachery of colleagues or family. They are uted by those jealous of their grandeur; they are pilloried, I by the enemy. Terrorists have set a watch on their houses : to destroy them before they can ascend to their thrones. Uy, along with delusions, patients may have isolated ations. Grandiose patients hear a chorus of angels singing [raises; the persecuted patients hear the resentful muttering rious crowd.

Hyperactivity becomes more pronounced, and the patient's behavior may begin to fragment. Impulses come at cross purposes, and patients, though increasingly active, may be unable to complete anything. Fragments of activity abound: patients may run, hop in place, roll about the floor, leap from bed to bed, race this way and then that, or repeatedly change their clothes at a furious pace.

Occasionally, patients in acute mania may evidence a passing fragment of insight: they may suddenly leap to the tops of tables and proclaim that they are "mad," then laugh, lose the thought, and jump back into their pursuits of a moment ago. Some may devote themselves to writing, flooding reams of paper with an extravagant handwriting, leaving behind an almost unintelligible, tangential flight of written ideas. Patients may dress themselves in the most fantastic ways. Women may decorate themselves with garlands of flowers and wear the most seductive of dresses. Men may be festooned with ribbons and jewelry. Unrestrainable sexuality may come to the fore. Patients may openly and shamelessly proposition complete strangers; some may openly and exultantly masturbate. Strength may be greatly increased, and sensitivity to pain may be lost.

Delirious Mania. The transition to delirious mania is marked by the appearance of confusion, more hallucinations, and a marked intensification of the symptoms seen in acute mania. A dreamlike clouding of consciousness may occur. Patients may mistake where they are and with whom. They cry out that they are in heaven or in hell, in a palace or in a prison; those around them have all changed—the physician is an executioner; fellow patients are secret slaves. Hallucinations, more commonly auditory than visual, appear momentarily and then are gone, perhaps only to be replaced by another. The thunderous voice of God sounds; angels whisper secret encouragements; the devil boasts at having the patient now; the patient's children cry out in despair. Creatures and faces may appear; lights flash and lightning cracks through the room. Grandiose and persecutory delusions intensify, especially the persecutory ones. Bizarre delusions may occur, including Schneiderian delusions. Electrical currents from the nurses' station control the patient; the patient remains in a telepathic communication with the physician or with the other patients.

Mood is extremely dysphoric and labile. Though some patients still are occasionally enthusiastic and jolly, irritability is generally quite pronounced. There may be cursing, and swearing; violent threats are made, and if patients are restrained they may spit on those around them. Sudden despair and wretched crying may grip the patient, only to give way in moments to unrestrained laughter.

Flight of ideas becomes extremely intense and fragmented. Sentences are rarely completed, and speech often consists of words or short phrases having only the most tenuous connection with the other. Pressure of speech likewise increases, and in extreme cases the patient's speech may become an incoherent and rapidly changing jumble. Yet even in the highest grades of incoherence, where associations become markedly loosened, these patients remain in lively contact with the world about them. Fragments of nearby conversations are interpolated into their speech, or they may make a sudden reference to the physician's clothing or to a disturbance somewhere else on the ward.

Hyperactivity is extreme, and behavior disintegrates into numerous and disparate fragments of purposeful activity. Patients may agitatedly pace from one wall to the other, jump to a table top, beat their chest and scream, assault anyone nearby, pound on the windows, tear the bed sheets, prance, twitter, or throw off their clothes. Impulsivity may be extreme, and the patient may unexpectedly commit suicide by leaping from a window.

Self-control is absolutely lost, and the patient has no insight and no capacity for it. Attempting to reason with the patient in delirious mania is fruitless, even assuming that the patient stays still enough for one to try. The frenzy of these patients is remarkable to behold and rarely forgotten. Yet in the height of delirious mania, one may be surprised by the appearance of a sudden calm. Instantly, the patient may become mute and immobile, and such a catatonic stupor may persist from minutes to hours only to give way again to a storm of activity. Other catatonic signs, such as echolalia and echopraxia and even waxy flexibility, may also be seen.

As noted earlier not all manic patients pass through all three stages; indeed some may not progress past a hypomanic state. Regardless, however, of whether the peak of severity of the individual patient's episode is found in hypomania, in acute mania, or in delirious mania, once that peak has been reached, a more or less gradual and orderly subsidence of symptoms occurs, which to a greater or lesser degree retraces the same symptoms seen in the earlier escalation. Finally, once the last vestiges of hypomanic symptoms have faded, the patient is often found full of self-reproach and shame over what he has done. Some may be reluctant to leave the hospital for fear of reproach by those they harmed and offended while they were in the manic episode.

In current nomenclature, those patients whose manic episodes never pass beyond the stage of hypomania are said to have "Bipolar II" disorder, in contrast with "Bipolar I" disorder wherein the mania does escalate beyond the hypomanic stage. Recent data indicate that bipolar II disorder may be more common than bipolar I disorder; however, should a patient with bipolar II disorder ever have a manic episode wherein stage II or III symptoms occurred, then the diagnosis would have to be revised to bipolar I.

Occasionally the age of the patient may influence the presentation of mania. Adolescents and children, for example, seem particularly prone to the very rapid development of delirious mania. On the other extreme, in the elderly, one may see little or no hyperactivity. Some elderly manic patients may sit in the same chair all day long, chattering away in an explosive flight of ideas. Mental retardation may also influence the presentation of mania. Here in the absence of speech one may see only increased, seemingly purposeless, activity.

Depressive Episodes

The depressive episodes seen in bipolar disorder, in contrast to those typically seen in a major depression, tend to come on fairly acutely, over perhaps a few weeks, and often occur without any significant precipitating factors. They tend to be characterized by psychomotor retardation, hyperphagia, and hypersomnolence and are not uncommonly accompanied by delusions or hallucinations. On the average, untreated, these bipolar depressions tend to last about a half year.

Mood is depressed and often irritable. The patients are discontented and fault-finding and may even come to loathe not only themselves but also everyone around them.

Energy is lacking; patients may feel apathetic or at times weighted down.

Thought becomes sluggish and slow. Patients cannot concentrate to read and cannot remember what they do read. Comprehending alternatives and bringing themselves to decisions may be impossible.

Patients may lose interest in life; things appear dull and heavy and have no attraction.

Many patients feel a greatly increased need for sleep. Some may succumb and sleep 10, 14, or 18 hours a day. Yet no matter how much sleep they get, they awake exhausted, as if they had not slept at all. Appetite may also be increased and weight gain may occur, occasionally to an amazing degree. Conversely, some patients may experience insomnia or loss of appetite.

Psychomotor retardation is the rule, although some patients may show agitation. In psychomotor retardation the patient may lie in bed or sit in the chair for hours, perhaps all day, profoundly apathetic and scarcely moving at all. Speech is rare; if a sentence is begun, it may die in the speaking of it, as if the patient had not the energy to bring it to conclusion. At times the facial expression may become tense and pained, as if the patient were under some great inner constraint.

Pessimism and bleak despair permeate these patients' outlooks. Guilt abounds, and on surveying their lives patients find themselves the worst of failures, the greatest of sinners. Effort appears futile, and enterprises begun in the past may be abandoned. They may have recurrent thoughts of suicide, and impulsive suicide attempts may occur.

Delusions of guilt and of well-deserved punishment and persecution are common. Patients may believe that they have let children starve, murdered their spouses, poisoned the wells. Unspeakable punishments are carried out: their eyes are gouged out; they are slowly hung from the gallows; they have contracted syphilis or AIDS, and these are a just punishment for their sins.

Hallucinations may also appear and may be quite fantastic. Heads float through the air; the soup boils black with blood. Auditory hallucinations are more common, and patients may hear the heavenly court pronounce judgment. Foul odors may be smelled, and poison may be tasted in the food.

In general a depressive episode in bipolar disorder subsides gradually. Occasionally, however, it may come to an abrupt termination. A patient may arise one morning, after months of suffering, and announce a complete return to fitness and vitality. In such cases, a manic episode is likely to soon follow.

Mixed-Manic Episode

Mixed-manic episodes are not as common as manic episodes or depressive episodes, but tend to last longer. Here one sees various admixtures of manic and depressive symptoms, sometimes in sequence, sometimes simultaneously. Euphoric patients, hyperactive and pressured in speech, may suddenly plunge into despair and collapse weeping into chairs, only to rise again within hours to their former elated state. Even more extraordinary, patients may be weeping uncontrollably, with a look of unutterable despair on their faces, yet say that they are elated, that they never felt so well in their lives, and then go on to execute a lively dance, all the while with tears still streaming down their faces. Or a depressed and psy-chomotorically retarded patient may consistently dress in the brightest of clothes, showing a fixed smile on an otherwise expressionless face. These mixed-manic episodes must be distinguished from the transitional periods that may appear in patients who "cycle" directly from a manic into a depressive episode, or vice versa, without any intervening euthymic interval. These transitional periods are often marked by an admixture of both manic , and depressive symptoms; however, they do not "stand alone , as episodes of illness unto themselves, but are always both | immediately preceded and followed by a more typical episode of homogenous manic or homogenous depressive symptoms. In contrast the mixed-manic episode "stands alone." It starts with mixed symptoms, endures with them, and finishes with them, and is neither immediately preceded nor immediately followed by an episode of mania or by an episode of depression.

At this point, before proceeding to a consideration of course, two other disorders that are strongly associated with bipolar disorder should be mentioned, namely alcoholism and cocaine addiction. During manic episodes, patients with these addictions are especially likely to take cocaine or drink even more heavily, and the effects of these substances may cloud the clinical picture.

COURSE

Bipolar disorder is an episodic or, as noted earlier, "cyclical" illness, being characterized in most patients by the intermittent lifelong appearance of episodes of illness, in between which most patients experience a "euthymic" interval during which they more or less return to their normal state of health.

The pattern and sequencing of successive episodes is quite variable among patients. The duration of the euthymic interval varies from as little as a few weeks or days to as long as years, or ; even decades. In contrast, however, to the extreme variability of the ³ euthymic intervals among patients, finding a certain regular pattern in the history of any given patient is not unusual. Indeed in ome patients the euthymic interval is so regular that patients can predict sometimes to the month when the next episode will occur, he postpartum period is a time of increased risk. Occasionally, jjne may also see a "seasonal" pattern, with manic episodes more :ly in the spring or early summer and depressive ones in the fall r winter.

Early on in the overall course of the illness the cycle length, or ne from the onset of one episode to the onset of the next, tends shorten. Specifically, whereas the duration of the episodes nselves tends to be stable, the euthymic interval shortens, so des come progressively closer together. With time, however, ; duration of the euthymic interval stabilizes. |Patients who have four or more episodes of illness in any one • are customarily referred to as "rapid cyclers." Although only 10% of all patients with bipolar disorder display such a jiern of rapid cycling, these patients are nevertheless clinically : important as they tend to be relatively "resistant" to many ntly available treatments. On the other extreme, the euthymic 1 may be so long, lasting many decades, that the patient dies jpre the second episode is "due," thereby having only one episode ness during an entire lifespan.

he sequence of episodes is also quite variable among patients, ply would one find a patient whose course is characterized by rly alternating manic and depressive episodes; most patients ' a preponderance of either depressive episodes or of manic | For example, in an extreme case a patient may have through-life perhaps six depressive episodes and only one manic one. fie other extreme, another patient might have up to a dozen des of mania and only one depressive one. Indeed one may nter a patient who has only manic episodes and never any ■sive ones. Such "unipolar manic" patients are very rare. In . a depressive preponderance is more common in females, f inanic one in males.

Noted earlier, for most patients the interval between episodes nic and free of symptoms. In at least a quarter of all cases, ', the interval may be "colored" by very mild symptoms, and tion of this "coloring," or its "polarity," correlates with the preponderance of episodes. For example, a patient with very mild subhypomanic symptoms during the interval is likely to have more manic episodes than depressive ones, and the converse holds true for the patients whose interval is clouded with mild depression or fatigue. In general, among women the preponderance of episodes are depressive; among men, manic.

In perhaps a quarter of all cases, the course exhibits "coupling." Here a manic episode may invariably and immediately be followed by a depressive one, or vice versa. In such cases the transition from one episode to the next may be marked by a mixture of symptoms, as if the various symptoms of the preceding episode trailed off at different rates, while the various symptoms of the following episode appeared also at varying rates, such that the two coupled episodes in a sense overlapped and interdigitated with each other, with this interdigitation presenting as the mixture of symptoms. Such "overlap" or transitional experiences must, as noted earlier, be distinguished from mixed-manic episodes proper, which stand on their own.

Occasionally, one may find bipolar patients in whom certain conditions, pharmacologic and otherwise, can more or less reliably precipitate a manic episode. These include serotoninergic agents such as tryptophan or 5-hydroxytryptophan; noradrenergic agents, such as cocaine, stimulants, or sympathomimetics, or situations in which noradrenergic tone is increased as in alcohol or sedative-hypnotic withdrawal or in the abrupt discontinuation of long-term treatment with clonidine; dopaminergic agents such as L-dopa or bromocriptine; and treatment with exogenous steroids, such as prednisone. Older antidepressants, such as the MAOIs and tricydics, are particularly notorious for precipitating manic episodes in bipolar patients, and some evidence suggests that these antidepressants, in addition to being capable of precipitating a manic episode, may also alter the fundamental course of bipolar disorder and increase the frequency with which future episodes occur: newer antidepressants, such as SSRIs, bupropion and venlafaxine, do not appear as likely to precipitate mania. Phototherapy may also induce manic episodes in those patients whose course exhibits a "seasonal pattern."

COMPLICATIONS

In mania, spending sprees and ill-advised business ventures may land patients in serious debt, or even bankruptcy. Hypersexuality may lead to unplanned and unwanted pregnancies or ill-considered marriages. A reckless exuberance may carry the patient past all speed limits and into conflict with the law; accidents are common. Irritable manics are likewise often in conflict with the law and may pick fights and create disputes with whomever they come in contact. Friendships may be broken, and divorce may occur.

Suicide occurs in from 10 to 20% of patients with bipolar disorder and appears to be more common in those who have only hypomanic episodes (i.e., those with bipolar II disorder) than in those whose manic episodes progress beyond the first stage (i.e., those with bipolar I disorder). Although most suicides appear to occur during episodes of depression, patients in a mixed-manic episode may be at an even higher risk.

The complications of a depressive episode are as outlined in the chapter on major depression.

ETYOLOGY

Genetic factors almost certainly play a role in bipolar disorder. A higher prevalence of bipolar disorder exists among the first-degree relatives of patients with bipolar disorder than among the relatives of controls or the relatives of patients with major depression, and the concordance rate among monozygotic twins is significantly higher than that among dizygotic twins. Similarly and most tellingly, adoption studies have demonstrated that the prevalence of bipolar disorder is several-fold higher among the biologic parents of bipolar patients than among the biologic parents of control adoptees.

Genetic studies in bipolar disorder have been plagued by failures of replication. In all likelihood, multiple genes on multiple different chromosomes are involved, each conferring a susceptibility to the disease.

Autopsy studies, likewise, have often yielded inconsistent results. Perhaps the most promising finding is of a reduced neuronal number in the locus ceruleus and median raphe nucleus.

Endocrinologic studies have yielded robust findings, similar to those found in major depression, including non-suppression on the dexamethasone suppression test and a blunted TSH response to TRH infusion.

Other robust findings include a shortened latency to REM sleep upon infusion of arecoline and the remarkable ability of intravenous physostigmine to not only bring patients out of mania but also to cast them down past their baseline and into a depression.

Taken together, these findings are consistent with the notion that bipolar disorder is, in large part, an inherited disorder characterized by episodic perturbations in endocrinologic, noradrenergic, serotoninergic and cholinergic function, with these in turn possibly being related to subtle microanatomic changes in relevant brainstem structures.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

In distinguishing bipolar disorder from other disorders, the single most useful differential feature is the course of the illness. Essentially no other disorder left untreated presents with recurrent episodes of mood disturbance at least one of which is a manic episode, with more or less full restitution to normal functioning between episodes. Thus if the patient in question has had previous episodes and if the available history is complete, then one can generally state with certainty whether the patient has bipolar disorder. However, these are two big "ifs," and in clinical practice history may either be absent or unobtainable, and herein arises diagnostic difficulty.

Occasionally a patient in a manic episode is brought to the emergency room by police with no other history except that he was arrested for disturbing the peace. If the patient is in the stage of acute mania with perhaps irritability and delusions of persecution, one might wonder if the patient is currently in the midst of the onset of paranoid schizophrenia or of its exacerbation. Here the behavior of the patient when left undisturbed is helpful: left to themselves, patients with paranoid schizophrenia often sit quietly, patiently waiting for the next assault, whereas patients with acute mania continue to display their hyperactivity and pressured speech. If the patient is in the stage of delirious mania, the differential would include an acute exacerbation of catatonic schizophrenia and also a delirium from some other cause. The quality of the hyperactivity seen in the excited subtype of catatonic schizophrenia is different from that seen in mania. The catatonic schizophrenic, no matter how frenzied, remains self-involved and has little contact with those around him. By contrast, manic patients, no matter how fragmented their behavior, show a desire and a compelling interest to be involved with others. In the highest grade of delirious mania, the patient, as noted earlier, may lapse into a confusional stupor. At this point, the differential becomes very wide, as discussed in the chapter on delirium. At times, a "cross-sectional" view of the patient, say in the emergency room, may allow an accurate diagnosis; however, a "longitudinal" view is always more helpful. As noted earlier, all patients in delirious mania or acute mania have already passed from relatively normal functioning through the distinctive stage of mania. Obtaining a history of this progression from normal through and past stage I hypomania allows for a more certain diagnosis.

The distinction between secondary mania and a manic episode of bipolar disorder is discussed in that chapter.

At times patients with schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type, may be very difficult to distinguish from those with bipolar disorder. Here a precise interval history is absolutely necessary. In schizoaffective disorder psychotic symptoms, such as delusions, hallucinations, or incoherence, persist between the episodes, in contrast to the "free" intervals seen in bipolar disorder. The interval psychotic symptoms seen in schizoaffective disorder may be very mild indeed, and thus close and repeated observation over extended periods of time may be required to ascertain their presence.

Cyclothymia may at times present diagnostic difficulty, for it also presents a history of discrete individual episodes. The difference is that in cyclothymia the manic symptoms are very mild. The possibility also exists, however, that the apparently cyclothymic patient is presenting, in fact, with a very long prodrome to bipolar disorder. Thus continued observation over many years may necessitate a diagnostic revision if a manic episode should ever occur.

The differential between a postpartum psychosis and a bipolar disorder that has become "entrained" to the postpartum period is discussed in that chapter.

The persistence of very mild affective symptoms between episodes might suggest, depending on the polarity of the symptoms, a diagnosis of dysthymia or of hyperthymia. Here, however, temporal continuity of these symptoms with a full episode of illness betrays their true nature, that of either a prodrome or of a condition of only partial remission of a prior episode.

The distinction

between a depressive episode occurring as part of a major depression and one

occurring as part of bipolar disorder is considered in the chapter on major depression.

depression.

The overall treatment of bipolar disorder is conveniently approached by considering, in turn, the treatment of the manic or mixed-manic episode first, then the treatment of the depressive episode, in each instance considering three phases of treatment: acute, continuation, and preventive. As will be seen, of all the medications useful in bipolar disorder, lithium is probably the best choice as it is the only one which has been shown to be effective for all three phases of treatment for both manic and depressive episodes.

Manic or Mixed-Manic Episodes

Acute Treatment. The acute treatment of a manic or mixed-manic episode almost always involves the administration of either a mood stabilizer (i.e., lithium, valproate or carbamazepine) or an antipsychotic (i.e., olanzapine, risperidone, aripiprazole, quetiap-ine or ziprasidone), or most commonly, a combination of a mood stabilizer and an antipsychotic. Although there are no hard and fast rules for choosing among these agents, some general guidelines may be offered. Certainly, if the patient has a history of an excellent response to a particular agent, then it should be seriously considered. Lacking such a history, and assuming there are no significant contraindications, the first choice among the mood stabilizers is probably lithium, as it has the longest track record. Divalproex is a close second, and, in the case of episodes with a significant depressive component, and certainly in the case of a mixed-manic episode, is actually superior to lithium. Another advantage of divalproex is the rapidity with which it becomes effective when a "loading" strategy is used, with patients often responding in a matter of days, in contrast with the week or two required with lithium. Carbamazepine is probably a little less effective than lithium, and, in general, is not as well-tolerated. Among the antipsychotics, the first choice is probably olanzapine in that it has the longest track record among these second generation agents in this regard and has also, in contrast with the other second generation agents, been shown to be effective in preventive treatment.

When symptoms are relatively mild, that is to say of hypomanic intensity, utilization of a mood stabilizer alone may be sufficient. However, when the mania has escalated into stage II or III, a mood stabilizer alone is generally not capable of controlling the clinical storm quickly enough, and in such cases it is common practice to initiate treatment with a combination of a mood stabilizer and one of the second-generation antipsychotics. In emergent situations, one may also employ one of the protocols outlined in the chapter on rapid pharmacologic treatment of agitation. Consideration should also be given to ÅÑÒ: bilateral ÅÑÒ is effective for mania and is indicated when the foregoing treatments are not successful or in life-threatening situations where urgent improvement is absolutely required. Should ÅÑÒ be utilized, lithium should not be administered concurrently, as it may enhance ECT-induced confusion.

Many manic patients require admission to a locked unit. Stimulation, including visitors, mail, and phone calls, should be kept to an absolute minimum, as it routinely exacerbates manic symptoms. Indeed, occasional patients in acute mania, still possessed of a few tattered shreds of insight, may demand to be put in seclusion. Isolated from all stimuli, they gradually improve, although their symptoms only partially abate. A calm, patient, and nonconfrontive manner is generally best; sometimes sharing the patient's jokes may be calming and helpful in enlisting cooperation. At times, however, a "show of force" may be necessary; indeed violent, irritable, and very agitated patients, though completely unfazed by routine measures, may calm down immediately upon the appearance of several formidable male orderlies, who, though calm, clearly "mean business." Restraints, however, may be required.

Continuation Treatment. Once acute treatment has been successful in bringing the manic symptoms under control, continuation treatment is begun. As noted earlier the average duration of ;the first manic episode is about 3 months, and that of a mixed-manic episode a little longer. The purpose of continuation treatment ³ to prevent a breakthrough of symptoms until such time as the episode itself has run its course. Generally this is accomplished by JMitinuing the regimen that was effective during the acute phase. . Lithium is used it may be necessary during the continuation to reduce the dose. In many patients even though the dose of dum is held constant, the blood level rises when the manic symptoms eventually come under complete control. The unexpected appearance of side effects to lithium may indicate this and should y°mPt a blood level determination. If ÅÑÒ were used, a mood stabilizer should be started after treatment is terminated.

If the patient decides not to enter into a preventive phase of treatment, one must estimate when the patient's current episode, in all likelihood, will go into a spontaneous remission. A prior history of manic episodes may provide some guidance here; if that is lacking, one is guided by the duration of an average episode, mentioned earlier. Clearly, if the patient is having breakthrough manic symptoms, no matter how mild, treatment should continue. Furthermore, even when the estimated date of remission has passed, one should continue treatment if the patient's life is unstable, and wait until a period of relative stability has occurred before exposing the patient to the risk, however small, of relapse. If lithium was utilized, it is important to taper the dose over a few weeks time, as it appears that abrupt discontinuation of lithium predisposes to a recurrence of mania. Although the need for tapering has not been demonstrated for the other agents, prudence dictates the use of a gradual taper here also.

Preventive Treatment. The decision to embark on preventive treatment is based on several factors including the following: frequency of episodes, severity of episodes, rapidity with which episodes develop, and side effects of the agent used. Frequent episodes, perhaps occurring more than once every 2 years, usually constitute an indication for preventive treatment; a frequency of one every 5 or 10 years, however, may be such that the risk to the patient of another episode is outweighed by the trouble of taking medicine and any attendant side effects. Severe episodes, however, no matter how infrequent, may warrant prevention. Whereas the patient's employer and family may be able to tolerate a manic episode limited to a hypomanic stage, a mania that enters a delirious stage is usually so destructive that it should be guarded against. Patients whose episodes tend to develop very slowly, over perhaps weeks or a month, may be able to "catch" themselves before their insight and judgment are lost. By making timely application for treatment, they may be able to bring the episode under control on an outpatient basis. Those whose episodes come on acutely over a few days or even hours, however, are defenseless and thus more appropriate for preventive treatment.

If preventive treatment is elected, then the patient should be treated with a mood stabilizer (lithium, divalproex or carbamazepine) or olanzapine. Among the mood stabilizers, lithium has the longest track record and is therefore a reasonable first choice. Divalproex and carbamazepine may also be considered; however, the data supporting the use of divalproex as a preventive agent are not that good and carbamazepine is generally not very well tolerated. If lithium is used, it is important to keep the serum level between 0.6 and 1.0 mEq/L. The optimum dose for valproate and for carbamazepine for prophylaxis has not as yet been determined; prudence suggests using a dose similar to that which was effective for continuation treatment. When "breakthrough" symptoms of mania occur it is imperative to determine the patient's thyroid status: hypothyroidism, even if manifest by only a slight rise in TSH, will blunt the response to any mood stabilizer, and must be corrected. When breakthrough mania occurs despite normal thyroid status and good compliance, consideration may be given to switching to monotherapy with another mood stabilizer or to using a combination of mood stabilizers such as lithium plus divalproex or lithium plus carbamazepine. Given the possibility of such "breakthrough" manias, it is generally prudent, in the case of reliable patients being maintained on a mood stabilizer, to prescribe a supply of adjunc-tive medication (e.g., olanzapine) to take at home in order to abort an episode and obviate the need for admission. In this regard, outpatients should be clearly instructed to call the physician should they even experience a "hint" of manic symptoms.

Olanzapine has recently been shown to be effective in preventive treatment, and thus may be considered as an alternative to a mood stabilizer. It must be borne in mind, however, that, as compared with the mood stabilizers, especially lithium, the experience with olanzapine is limited; furthermore, emerging data regarding the risks of diabetes and hyperlipidemia with olanzapine may also temper enthusiasm for the long-term use of this agent.

As noted in the section on course, various pharmacologic conditions, such as the use of sympathomimetics, the abrupt discontinuation of long-term treatment with donidine, and the like, may precipitate manic episodes, and these conditions should be avoided whenever possible. Furthermore, as noted earlier, insomnia, or simply voluntarily going without sleep, may also precipitate a manic episode, and consequently, good sleep hygiene should be promoted.

Recently it has been shown that cognitive behavioral therapy may, when used in conjunction with preventive pharmacologic treatment, reduce the frequency of breakthrough episodes. The mechanism here is not dear, and it also must be kept in mind that no form of psychotherapy is effective for either acute or continuation treatment of mania.

Depressive Episodes

Acute Treatment. When a depressive episode occurs in a patient with bipolar disorder the first step in the acute phase of treatment is to ensure that the patient is taking an antimanic drug, such as lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine, in a dose that would be effective in the acute treatment phase of mania. If the depression is not severe, one may want to wait 2 or 3 weeks to see if the depressive symptoms begin to clear, as this may often happen when one of these three agents is used. When depressive symptoms persist or when they are so severe to begin with that one cannot wait, one may add an antidepressant or consider adding lamotrigine or perhaps topiramate. Traditionally an antidepressant has been used; however, though effective, all the antidepressants entail the risk of precipitating a manic episode; a strategy for choosing and utilizing an antidepressant is discussed in the chapter on major depression. Neither lamotrigine nor topiramate carry a risk of inducing a manic episode, and between the two, the evidence for the effectiveness of lamotrigine is much stronger. In mild cases of depression, one may also consider the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Continuation Treatment. Once the depressive symptoms are relieved, treatment should be continued until the patient has been asymptomatic for a significant period of time. If an antidepressant were added to a mood stabilizer, one should probably consider discontinuing the antidepressant after the patient has been asymptomatic for a matter of months. Given the ongoing risk of a "precipitated" mania, it is preferable to discontinue the drug as soon as possible: if depressive symptoms recur, one may always restart it. In the case of topiramate or lamotrigine, the optimum duration of continuation treatment is not clear. Prudence suggests that if one knows, from history, how long the patient's. Depressive episodes tend to last, that treatment be continued somewhat past the expected date of spontaneous remission of the depression.

Preventive Treatment. Lithium, carbamazepine and lamotrigine are all effective in preventing future depressive episodes. Preventive treatment with antidepressants in bipolar disorder is generally not justified, given the ongoing risk of precipitating a manic episode.

Other Treatment Considerations

Pregnancy.

Pregnancy constitutes a special challenge in the treatment of bipolar disorder.

None of the mood stabilizers are safe during pregnancy (especially the first

trimester). First generation antipsychotics, such as haloperidol, are probably

less teratogenic-the teratogenic potential of olanzapine is not as yet clear.

If mania does occur during pregnancy, then the risks to the fetus must be

carefully weighed against  the risks

inherent in a manic episode. ÅÑÒ should be carefully considered given that,

with proper anesthetic technique, it is of low risk to the fetus.

the risks

inherent in a manic episode. ÅÑÒ should be carefully considered given that,

with proper anesthetic technique, it is of low risk to the fetus.

Bipolar women currently in the preventive phase of treatment may often be safely managed into and through a planned pregnancy. Preventive treatment may be continued up to a few days before conception is attempted. If conception does not occur, preventive treatment is restarted and continued until the couple again wishes to conceive. Once conception does occur, preventive treatment is withheld, to be restarted immediately upon delivery; indeed, barring obstetric complications, it should be restarted within hours. In collaboration with the obstetrician, adjunctive treatment is then made available should manic symptoms appear. In cases where the risk of a relapse of mania is high and outweighs the risk to the fetus, one may consider restarting a mood stabilizer after the first trimester. With regard to breast feeding, no firm advice can be given: although maternal use of lithium, valproate and carbamazepine have all been rarely associated with adverse effects in breast-fed infants, large, controlled studies are lacking. Consequently the decision to breast feed or not should be made in light of the entire clinical picture, including the mother's illness and response to treatment.

Substance Use. As noted earlier, alcohol abuse or alcoholism and cocaine addiction are not infrequently associated with bipolar disorder, and these must also be treated.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy – term for number of disorders characterized by various combinations of the following: periodic sensory or motor seizures (or epileptic equivalent) accompaned by an abnormal encephalogram (EEG), wich or with actual convulsions, clouding of or loss of consciousness, and motor, sensory or cognitive malfunctions.

Can anyone have epilepsy or not? Virtually everyone can have a seizure under the right circumstances. Each of us has a brain seizure threshold which makes us more or less resistant to seizures. Seizures can have many causes, including brain injury, head trauma, poisoning, or stroke. And these factors are not restricted to any age group, sex, or race and neither is Epilepsy.

Varieties of Epilepsy

There are several forms of epilepsy. Most people will have seen someone suffer a major epileptic seizure, suddenly losing consciousness, jerking the arms and legs, etc. But there are other types of epilepsy - for example, one common form of epilepsy in children merely consists of staring blankly and losing contact with the surroundings for a few seconds.

Ideopatic epilepsy (or cryptogenic epilepsy) - any epilepsy for which there is no clear-cut cause.

Temporal epilepsy – type of epilepsy in which the focus of the dysfunction localize in the temporal lobe of the cortex.

History

In Ukrainian language epilepsy called also „÷îðíà õâîðîáà” (“black disease”) becouse pathients with epileptic seizures have dark-violet or black color of faces.

Does Epilepsy strike at any particular age?

Epilepsy can strike anyone at any age. But some age groups are more susceptible than others.

Most people who develop seizures during their earlier years tend to experience a reduction in the intensity and frequency of their seizures as they grow older. In many cases the Epilepsy will disappear completely.

50% of all cases develop before 10 years of age.

Aura – a subjective experience that frequenty precede an epileptic seizer. The aura may occure any time from a few hourse to several seconds prior to onset.

Psychic Auras

Type

Symptoms

Probable Source

Dysphasica

Nonfluent

Left perisylvian language areas

Impaired comprehension

Dysmnesic

Déjà vu, déjà vécu, déjà pensé, déjà entendu, jamais vu, etc., prescience, illusion of memory

Mesobasal temporal,b especially on right

Cognitive

Dreamy state, altered time sense, derealization, depersonalization

Mesobasal temporal and temporal neocortex

Forced thinking, forced actions, and altered or obscure thoughts

Frontal association cortex

Affective

Fear, anxiety, apprehension, depression, pleasure, displeasure

Mesobasal temporal and temporal neocortex

Illusionsc

Macropsia, micropsia, teleopsia, movement, metamorphopsia, increased color intensity, increased stereopsis intensity

Lateral superior temporal neocortex, especially on right for visual illusions

Hallucinations

Structured, hallucinatory remembrances, autoscopy

Mesobasal temporal and temporal neocortex

a)Does not include speech arrest or simple vocalizations.

b)Includes hippocampus, amygdala, and the parahippocampal gyrus.

c)Includes interpretive (size, motion, shape, and stereopsis) or experiential (elements of past experience or involvement).

The famoust russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky had “ecstatic auras” in which he felt in perfect harmony with the entire universe and “would give 10 years of this life, perhaps all of it, for a few seconds of such bliss.” The experience of epileptic derealization or depersonalization could impair reality testing. Another psychic aura is “forced thinking,” characterized by recurrent intrusive thoughts, ideas, or crowding of thoughts. Forced thinking must be distinguished from obsessional thoughts and compulsive urges. Epileptic patients with forced thinking experience their thoughts as stereotypical, out-of-context, brief, and irrational, but not necessarily as ego dystonic.

What is a seizure?

One of the best available classification of seizures is that proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy ("seizure" is an alternative term for "epileptic attack").

Partial (focal, local) seizures

Simple partial seizures

Motor, somatosensory, autonomic, or psychic symptoms

Complex partial seizures

Begin with symptoms of simple partial seizure but progress

to impairment of consciousness

Begin with impairment of consciousness

Partial seizures with secondary generalization

Begin with simple partial seizure

Begin with complex partial seizure (including those

with symptoms of simple partial seizures at onset)

Generalized seizures (convulsive or nonconvulsive)

Absence (typical and atypical)

Myoclonus

Clonic

Tonic

Tonic-clonic

Atonic/akinetic

Unclassified

Generalised Seizures

Absence seizures are not dramatic - in fact, they may not even be noticed at first. This form of epilepsy was previously known as "petit mal", (from French language meaning "little sickness" ). These seizures are extremely rare in adults. Petit mal seizures begins in childhood, between the ages of 5 and 10. It may cease at puberty, or continue throughout adult life. Typically, the child may be seen to stare vacantly for a few seconds, often fluttering the eyelids briefly, and seeming to be out of contact with surroundings. The classic triad of petit mal seizures includes the classic absence, myoclonic seizures or lightning jerks (including salaam seizures), and atonic seizures. The attack is accompanied by a bilaterally synchronous EEG wave and spike formations at about 3 per second and is often easily brought on by hyperventilation.

The child does not fall to the ground, and recovery is prompt, although the attacks may recur repeatedly, up to many times in the same day. The school work then suffers, and the child may be accused wrongly of "daydreaming". Petit mal seizures can be a problem if there are large numbers of them in sequence or during the course of the day.

Tonic-clonic seizures were previously called "grand mal" attacks (from French language meaning "big sickness"). This type of episodes looking very dramatic. There may be a brief warning consisting of a feeling of sinking or rising in the pit of the stomach, or the person may cry out or groan before losing consciousness completely. The limbs become stiff and rigid, and breathing stops, causing the lips to go blue. The eyes are rolled upward, and the jaws are clenched - if the tongue or lips are in the way, they will be bitten. This "tonic phase" is followed, within 30 to 60 seconds by the "clonic phase", in which the body is a shaken by a series of violent, rhythmic jerkings of the limbs. These usually cease after a couple of minutes. The person then recovers consciousness, but may be confused for several minutes, and wishes to sleep for an hour or two afterward. Headache and soreness of the muscles which have contracted so violently are commonly experienced for a day or more after the attack.

GRAND MAL SEIZURES. These may have a brief aura and are often initiated by a cry, presumably due to forced expiration of air. The cry is followed by or is simultaneous with the loss of consciousness, which is followed by falling to the floor, often with physical injury, and the advent of extreme tonic spasm, the extensor muscles dominating the flexors. This is usually followed by a clonic phase in which there is alternating flexion and extension of the body musculature, which may lead to biting of the tongue or mouth or further injury to the head.

Cyanosis is often marked until the seizure terminates, with deep noisy breathing and often with profuse sweating and salivation. There may be relaxation of the sphincters, with loss of urine or feces during the seizure, and in the male the ejaculation of semen, usually with erection, may occur. The EEG during this period is dominated by high voltage and fast activity in all leads and often terminates with an isoelectric period during which little or no spontaneous electrical activity is visible. The patient may waken into a confused state described as the postictal twilight state; he may become perfectly alert and oriented although somewhat slowed down and dull, or he may lapse into apparently normal sleep for some minutes or an hour or two. On recovery he usually complains of muscular aches and often of a severe headache. A marked bulimia may occur on respvery, eading the patient to ingest copious volumes of food or liquid. With complete recovery, there may well be feelings of depression and despair, often in reaction to the reality aspects of the seizure and social embarrassment.

Other varieties of generalised epilepsy are uncommon. They include:

Myoclonic seizures where there may be sudden, symmetrical, shock-like contractions of the limbs, which may or may not be followed by loss of consciousness.

Atonic seizures, in which there is momentary loss of tone in the muscles of the limbs, leading to sudden falling to the ground or dropping of the head. The pattern is most often seen in children who have suffered injury to the brain, through lack of oxygen at birth, meningitis in infancy, etc.

Tonic seizures, where stiffening of the abody (arching the back) is the predominant feature. This type of attack may or may not be followed by loss of consciousness. It too is most commonly seen in children who have suffered some form of major insult to the brain.

Electroencefalogram (EEG) – a record of the changes in elecrical potential of the brain.

The diagnosis of epilepsy is established by at least one specialist in epilepsy.

The presence of epileptic automatisms are documented by history and by closed circuit television EEG telemetry.

The presence of violence during epileptic automatisms is verified in a videotape-recorded seizure in which ictal epileptiform patterns are also recorded on the EEG.

The aggressive act is characteristic of the patient's habitual seizures, as elicited by history.

A clinical judgment is made by the epilepsy specialist attesting to the possibility that the aggressive act was part of a seizure.

TREATMENT

Anticonvulsant Medications

In the treatment of psychiatrically disturbed epileptic patients, a first consideration is the behavioral effects of anticonvulsant medications. Carbamazepine, valproate, lamotrigine, and gabapentin (Neurontin) have significant antimanic and modest antidepressant properties, probably through mood stabilization effects. They have some efficacy in the long-term prophylaxis of manic and depressive episodes. Carbamazepine and valproate may also ameliorate some dyscontrolled, aggressive behavior in brain-injured patients. Clonazepam, in addition to its anxiolytic properties, can serve as a supplement to other antimanic therapies. Gabapentin also decreases anxiety and improves general well-being in some epilepsy patients. Carbamazepine and ethosuximide may have value for borderline personality disorder.

Encephalopathic changes occur at toxic levels of all anticonvulsant drugs. Even at therapeutic levels, barbiturates may need discontinuation because of drug-induced depression, suicidal ideation, sedation, psychomotor slowing, and paradoxical hyperactivity in the very young and the very old. Gabapentin may induce aggressive behavior or hypomania, and vigabatrin (Sabril) may precipitate depression. In addition, clinicians need to be aware of the potential emergence of psychopathology on withdrawal of anticonvulsant medications. Anxiety and depression are the most common emergent symptoms, but psychosis and other behaviors may also occur.

Psychotropic Medications

A second consideration is the seizure threshold lowering effect of psychotropic medications. This is usually not a problem but can occasionally reach clinical significance in poorly controlled epilepsy. Psychotropic drugs are most convulsive with rapid introduction of the drug and in high doses. Clozapine (Clozaril), for example, has induced seizures in 1.0 to 4.4 percent of patients, particularly when the dose was rapidly increased. When initiating psychotropic therapy, it is best to start low and go slow while monitoring anticonvulsant levels and EEGs.

Potential

Antipsychotic

Antidepressant

Other Psychotropic

High

Chlorpromazine (Thorazine)

Bupropion (Wellbutrin)

Clozapine (Clozaril)

Imipramine (Norfranil)

Maprotiline (Ludiomil)

Amitriptyline (Elavil)

Amoxapine (Asendin)

Nortriptyline (Aventyl)

Moderate

Most piperazines

Protriptyline (Vivactil)

Lithium (Eskalith)

Thiothixene (Navane)

Clomipramine (Anafranil)

Low

Fluphenazine (Prolixin)

Doxepin (Sinequan)

Ethchlorvynol (Placidol)

Haloperidol (Haldol)

Desipramine (Norpramin)

Glutethimide (Doriden)

Loxapine (Loxitane)

Trazodone (Desyrel)

Hydroxyzine (Vistaril)

Molindone (Moban)

Trimipramine (Surmontil)

Meprobamate (Equanil)

Pimozide (Orap)

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Methaqualone (Quaalude)

Thioridazine (Mellaril)

Risperidone (Risperdal)

Olanzapine (Zyprexa)

Ziprasidone (Geodon)

Drug Interactions

A third treatment consideration is the potential for interaction of anticonvulsant and psychotropic medications. Most commonly, an anticonvulsant drug increases the metabolism of a psychotropic drug with a consequent decrease in its therapeutic efficiency. Conversely, withdrawal of anticonvulsant drugs can precipitate rebound elevations in psychotropic levels. Moreover, the initiation of a psychotropic drug may result in competitive inhibition of anticonvulsant metabolism with elevations of anticonvulsant levels to toxicity.

Carbamazepine (Tegretol)

SPS, CPS, GTCS

Potentially decreased

Decreased

Phenytoin (Dilantin)

SPS, CPS, GTCS

Potentially decreased or increased, rarely toxic levels

Decreased

Phenobarbital (Barbita) and primidone (Myidone)

SPS, CPS, GTCS

Potentially decreased

Significantly decreased

Valproic acid (Depakene)

CPS, GTCS, absence

Potentially increased, rarely toxic levels

Potentially decreased

Ethosuximide (Zarontin)

Absence

None known

None known

Clonazepam (Klonopin)

Myoclonic

Potentially decreased

Potentially decreased

Gabapentin (Neurontin)

Add on: CPS, SPS, ±2nd GTCS

No significant interactions known

No significant interactions known

Lamotrigine (Lamictal)

Add on: CPS, SPS, ±2nd GTCS

No significant interactions known

No significant interactions known

Vigabatrin (Sabril)

Add on: CPS, SPS, ±2nd GTCS

No significant interactions known

No significant interactions known

Tiagabine (Gabitril)

Add on: CPS, SPS, ±2nd GTCS

No significant interactions known

No significant interactions known

CPS, complex partial seizure; GTCS, generalized tonic-clonic seizure; SPS, simple partial seizure.

a)Antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs; lithium and the minor tranquilizers have few drug interactions with anticonvulsant drugs.

Compared to older drugs, the new anticonvulsant medications have fewer potential interactions with psychotropic medications. Gabapentin, lamotrigine, vigabatrin, and tiagabine (Gabitril) are relatively free of enzyme-inducing or -inhibiting properties. Felbamate (Felbatol), however, has been withdrawn in the United States, because some patients developed fatal aplastic anemia and liver disease.

Surgery

Epilepsy surgery is a fourth treatment consideration and is limited to patients with medically intractable seizures. The main operation involves resection of epileptogenic tissue by removal of 4 to 6 cm of the anterior temporal lobe. More than 80 percent of temporal lobectomy patients experience some reduction in their seizure frequency, and more than 50 percent of patients are entirely seizure free. Removal of the amygdala and most of the hippocampus may have postoperative behavioral effects. Some patients have an anomia or a verbal memory deficit after resection of the dominant hemisphere, and patients occasionally develop a transient postoperative affective disorder. Others experience a reduction in postictal psychosis, depression, and hyposexuality, but epileptic patients may continue to develop interictal psychosis, personality changes, and suicidal behavior even long after the temporal lobectomy. Moreover, patients with preoperative psychotic symptoms are at higher risk for a poor surgical outcome and postoperative psychosis.

Less common epilepsy surgeries include resection of extratemporal lesions, removal of the epileptogenic hemisphere, and ligation of the corpus callosum. Corpus callosotomy, which aims to prevent the interhemispheric spread of seizures, results in a unique, transient disconnection syndrome of mutism, apathy, agnosia, apraxia of the nondominant limbs, difficulty naming, and writing with the nondominant hand.

Seizure Management

In treating the neuropsychiatric disorders of epilepsy, a final consideration is altering the seizure management itself. In addition to the occasional behavior alleviated by strict seizure control, allowing seizures under carefully controlled conditions, much like ECT, relieves some cases of periictal psychosis, depression, or other behaviors.

Epilepsy Surgery

A single review article devoted to the subject of surgery for the treatment of epilepsy can only serve as a brief introduction. The field of epilepsy surgery is too large a topic to be adequately covered in this article. This assertion is evidenced by the facts that postresidency fellowships are available for neurosurgeons that wish to subspecialize in epilepsy surgery and that many neurosurgeons perform epilepsy surgery almost exclusively. More comprehensive information is available in several encyclopedic textbooks published on this subject.

Anteromedial temporal resection (AMTR) was chosen because it is the most frequently practiced surgery for a common and well-described disorder—mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. It serves as a model for other focal resections.

Corpus callosotomy is the only applicable surgery for generalized epilepsy syndromes.

Multiple subpial transection (MST) is new and may gain popularity.

First presented in this article are definitions of basic concepts; then, the general workup of patients with routine diagnostic tests is discussed. Specific surgical techniques follow.

Reasons for considering surgical intervention

Although intracranial surgery involves inherent risks, these risks do not equal the risks of uncontrolled seizures. The morbidity and mortality of seizures include accidental injury; cognitive decline; sudden death; and psychological, social, and vocational impairment.

Accidental injuries commonly include fractures, burns, dental injuries, lacerations, and head injuries.

Mortality rates for patients with nonconvulsive and convulsive seizures far exceed those for age-matched controls. Among patients with poorly controlled epilepsy, sudden unexplained death in epilepsy can reach a rate of 1 death per 500 patients per year.

Cognitive decline over time has been demonstrated to occur in patients with certain epilepsy syndromes who have recurrent convulsive seizures or episodes of status epilepticus.

Both depression and anxiety are very common among patients with medically refractory epilepsy.

Intractable epilepsy prevents driving and reduces fertility and marriage rates.

Vocational issues include inability to be employed or, if employed, underemployment.

Criteria for surgery

A candidate for epilepsy surgery must (1) have not attained adequate seizure control with sufficient trials of AEDs and (2) have a reasonable chance of benefiting from surgery. Adequate AED trials must be considered within the context of the patient's circumstances and form of epilepsy.

Strategy for a surgical workup

The presurgical evaluation for epilepsy has changed substantially in the past few decades, most notably since the advent of long-term video-EEG monitoring in the late 1970s, advanced neuroimaging, and subspecialty epilepsy centers. The presurgical evaluation requires input from many members of an integrated team, which includes neurologists, neurophysiologists, neuropsychologists, social workers, radiologists, nurses, and epilepsy neurosurgeons. A surgical plan is usually developed at a multidisciplinary team conference. This allows open discussion among multiple experts so that the surgical approach is unique and is tailored to the individual's personal needs and epilepsy syndrome. When all presurgical information points to a unifying location and theory regarding focal seizure onset (also referred to as concordant data), then the patient may proceed directly to resective surgery. When data are inadequate to define a resective strategy, then diagnostic intracranial electrodes may be considered to further define the syndrome or site of seizure onset prior to any resective surgery.

Diagnostic Phase

A presurgical diagnosis is made after a classification of the seizure types and specific epilepsy syndrome that affect the patient. The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) recognizes approximately 10 types of recurrent seizures and approximately 40 forms of epilepsy syndromes. Both classification schemes reflect the fact that seizures and epilepsies naturally fall into 2 major groups, based on the site of seizure onset in the brain, either (1) focal (partial, localization-related) or (2) generalized (ILAE, 1981; Engel, 2001).

The signs and symptoms (semiology) experienced by the patient and the EEG pattern recorded at ictal onset determine a seizure diagnosis. This process begins by recording a careful history. For example, an event that is initiated with a blank stare and arrest of motion and then progresses to the development of automatisms (ie, automatic repetitive semipurposeful movements) is likely a complex partial seizure. However, even under the best circumstances, a diagnosis based solely on the history can be incorrect. The most accurate method of seizure diagnosis is with long-term video-EEG monitoring.

Below is a simplification of the international classification of epileptic seizures.

Partial seizures (seizures that begin focally)

Simple partial seizures (full consciousness, not impaired)

Complex partial seizures (consciousness impaired)

Partial seizures that progress to generalized tonic-clonic seizures

Generalized seizures (seizures that arise diffusely)

Absence seizures

Atypical absence seizures

Clonic seizures

Tonic seizures

Tonic-clonic seizures

Myoclonic seizures

Atonic seizures

Unclassified seizures

An epilepsy syndrome diagnosis combines the seizure type with its associated MRI, physical examination, genetic, and other features. For example, if the seizure described above (1) has correlative EEG epileptiform patterns (interictal spikes or sharp waves) and ictal discharges over the right temporal lobe, (2) occurs in a patient who had a febrile seizure as a child but no family history of epilepsy, and (3) is associated with ipsilateral atrophy and increased signal of the hippocampus on an MRI, it is likely a complex partial seizure of right mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. The greatest value of a syndrome diagnosis is to provide a prognosis. In the above example, if the patient is right-handed with normal intelligence, he or she has excellent odds of becoming seizure free after right-sided anteromedial temporal resection (AMTR).

Structural and metabolic brain imaging

Because seizures may result from cortical lesions or malformations, neuroimaging can often help identify and localize this damage and, therefore, the focus.

Skull radiography: Routine skull films are of little value.

CT scanning: MRI has replaced routine CT scanning because of superior imaging. The one exception is that CT scanning demonstrates intraparenchymal calcium and acute bleeding better than MRI. This may be helpful in distinguishing certain types of tumors or CNS syndromes, such as tuberous sclerosis.

MRI: Brain MRI unquestionably is the best structural imaging study. Every surgical evaluation should include a complete study with special thin-cut magnified views perpendicular to the axis of the temporal horn. These views can demonstrate mesial temporal sclerosis.

Positron emission tomography (PET): Unlike MRI or CT scanning, PET scanning demonstrates brain glucose metabolism rather than structure. The typical finding from an interictal scan is hypometabolism in the region of the epileptic focus and, if the scan is obtained during a seizure, the typical finding is hypermetabolism from the focus.

Single-photon emission tomography (SPECT): SPECT scanning helps visualize blood flow through the brain and, therefore, has been evaluated as another method for localizing the epileptic focus.

Interictal SPECT scans are less accurate than ictal scans. However, ictal scans are problematic because the tracer must be injected within the initial seconds of seizure onset. This requires that the radionucleotide be available on the monitoring ward 24 hours per day with personnel licensed (under state law) to administer intravenous injections.

A newer methodology that has greater accuracy than either ictal or interictal SPECT scanning is subtraction ictal-interictal SPECT co-registered to MRI (SISCOM). This requires obtaining scans (separated by at least 48 h to accommodate radionucleotide washout) during an interictal period and within seconds of seizure onset. These scans are then subtracted from one another with the use of specialized computer software. This leaves a better indication of the cortical area of ictal onset. This subtracted scan can then be co-registered onto the patient's MRI to provide support for the location of the focus.

EEG evaluation